Les tableaux reunis par le F.R.A.C. Limousin constituent une retrospective de l’oeuvre de John Currin. Compte tenu de son jeune age, il est ne en 1962, ce choix pourrait paraitre outre. Il a le merite, au contraire, de mettre simultanement en evidence les lignes directrices du travail et l’impact perturbateur engendre par la rencontre d’une peinture <<bien faite>> et d’une certaine monstruosite.

Ces tableaux frappent avant tout par la suite d’anomalies qu’ils presentent. Leur genre – des portraits, des nus – comme leur format de chevalet, peu usites aujourd’hui si on exclut les <<peintres du dimanche>>, paraissent anachroniques. La facture lisse, precise et vigoureuse tout comme le realisme quelque peu veriste qui caracterisent ces oeuvres, ne le sont pas moins.

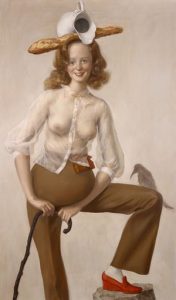

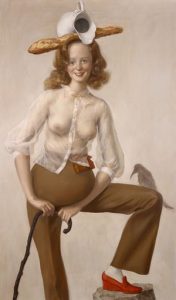

Les figures sont toutes plus ou moins difformes. Leur tete, leur corps sont disproportionnes les uns par rapport aux autres et frolent parfois la caricature. Le point de vue souvent situe relativement bas leur confere une monumentalite theatrale, derisoire mise en scene de leur etat chetif, malingre.

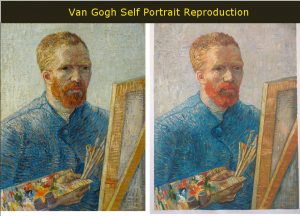

Les styles de Courbet, Derain, Picabia, Dix, entre autres, sont evoques a propos de la peinture de Currin. On peut ajouter celui des Limners americains, ceux des effigies populaires et des chromos en tous genres. Nude, avec ses formes et sa carnation, ses cheveux longs et roux sur fond bleuvert, son derriere tendu vers nous, emprunte autant a Renoir qu’aux pin-ups aguicheuses des calendries de camionneurs. Ce qu’il faut bien appeler le style Currin resulte d’une concentration de references qui s’accumulant outre mesure acquiert une qualite impersonnelle et signale l’artefact.

Les portraits realises par Currin ne comportent aucune indication d’une quelconque condition sociale, d’une activite propre a une personne. Ils ont pour nom Untitled, Skinny Woman, The Old Guy, parfois Jamita, le plus souvent, ils sont fabriques a partir d’images superposees et projetees. La demarche garantit d’une part l’anonymat du modele (mais de quel modele?), d’autre part confere a la figure une nature mitigee, car les images utilisees associent souvent sujets masculins et feminins. L’etrangete de cette image, son decalage recurrent par rapport a un eventuel original, dement la fonction de representation. Manifestement, ces <<portraits>> n’ont pas pour objet de perenniser le souvenir d’un individu specifique, ne renvoient a aucun referent particulier dont ils seraient le tenant lieu. Des lors, l’enjeu reside davantage dans la possibilite de faire, aujourd’hui, un tableau, objet depeint, support d’image.

La singularite des figures qu’il convoque ne reside plus dans leur unicite, leur identite. Avant tout composites, elles rassemblent en elles les traits de multiples modeles que l’artiste collectionne. Images peintes, photographiees ou filmees, elles ont pour point commun d’etre destinees a la diffusion. Elles ne vehiculent pas seulement les canons d’une beaute ideale mais aussi les differents codes et modes de representation qui s’attachent a l’image de la figure humaine sans lesquels celleci ne saurait etre. Plus ou moins discrets, toujours familiers, ils constituent autant de stereotypes que Currin assemble, compose, pour construire une nouvelle image; image qui ne doit pas se reduire a un cliche bien qu’elle ne puisse plus etre completement originale. De meme, l’artiste reprend des genres picturaux comme autant d’archetypes qui s’incarnent ici dans des personnages. Devenus paradigmes, ils fonctionnent un peu comme les totems du tableau et de l’image peinte.

Les genres retenus comme les themes des derniers tableaux se concentrent sur la figure humaine. Dans ces tableaux apparemment anthropocentriques, elle n’est plus qu’un motif qui est d’abord un pretexte a travailler sur l’image. Generalement place au centre du tableau, il emerge du fond qui, systematiquement, recouvre ses limites et de ce fait les reprecise. Plus synthetique, il apparait aussi plus concentre et plus plat. Paradoxalement, ce motif semble se detacher du fond et venir en avant, comme colle sur la surface, encore tire a nous par la densite particuliere d’un point colore (les yeux des jeunes filles, le bouton d’une robe place incongrument sur un sein), par un objet ou par des membres (les mains dans The Wizard par exemple) qui occupent une place trop centrale. Ces memes elements incitent le spectateur a deplacer son regard des visages, des yeux, vers un autre endroit du tableau. Le point de vue impose par l’artiste se confirme ici dans une relation qui n’est plus de l’ordre du face a face. Ces figures se laissent voir mais ne nous renvoient pas notre regard. Reifiees, elles corroborent leur statut d’image et par suite celui du tableau avec lequel elles font bloc.

Issu d’images, lui-meme image, le motif fait appel a un modele deja mediatise, a une ou plusieurs representations mentales. Ce qui en resulte participe de la mise en abyme d’un modele dont l’original est fort lointain sinon tout a fait perdu. Qui dit mediatisation, dit interpretation, refabrication. Cet enchainement ne va pas sans entrainer des decalages. Une seule figure concentre sous sa surface une succession de mouvements et son caractere mutant arrete immanquablement notre regard. Est-ce a dire qu’il y aurait quelque part un modele conforme, donc un original considere comme canonique auquel nous serious tout prets a nous assimiler? Ce n’est pas certain. Et pourtant, face a ces images qui ne nous refletent pas mais en appellent seulement a nous-memes, nous ne pouvons nous empecher de nous sentir concernes, de nous percevoir comme sources et de recevoir ces representations comme autant de deformations.

Captured 2/17/2015. UNVARNISHED. For press ONLY, not for catalog.

Quelques artistes de la generation de Currin et de la precedente ont investi le champ de la representation humaine de manieres diverses. Mais contrairement a eux, Currin conserve aux images qu’il cree un potentiel d’affects exploite notamment dans les oeuvres les plus recentes qui closent l’exposition. Celles-ci disent plus fortement l’aspect mental de la representation. The Wizard et The Purification introduisent dans l’oeuvre des microfictions qui evoquent un etat plus qu’une action. Plus affectees, elles restaurent une relation entre les figures feminines et masculines qui n’est pas sans evoquer certains themes de la peinture. Ce qui lie les deux personnages de The Wizard releve du sentiment qui attirait les vieillards autour de Su zanne. Si le contact s’est substitue au regard des vieillards, il n’a pas aboli la distance entre le personnage qui touche en aveugle et la poitrine de la femme. L’ambiguite de la nature comme de la categorie des personnages y est plus eclatante et deborde sur le lien qui s’ebauche. La sexualite n’a jamais ete absente des tableaux de Currin, y compris par defaut. Elle se laisse voir maintenant en surface, sans pour autant enlever au mystere.

La demesure des representations insiste plus clairement sur la subjectivite de la vision, sur la valeur symbolique que recouvrent les images. Si celles-ci nous heurtent en revendiquant leur statut de chose, elles disent aussi la part subjective de psychologie qui conditionne toute representation mentale. Ce n’est pas la la moins genante de leurs caracteristiques tout comme cette ambivalence n’est la moins importante des anomalies distillees par l’artiste.

L’oeuvre se situe dans l’exces du trait, de la reference, du caracterise, de l’absence et de l’impersonnalite. Cette surabondance pourrait bien etre une tentative de dire mais aussi de palier une vacuite nee d’un trop-plein qu’il importe de depasser pour continuer a figurer. En construisant sur le passif contemporain, sur une culture de l’image, en disant l’artefact mais en reintroduisant l’affect, Currin semble fort bien s’y employer.